Authentic news,No fake news.

In April, a judge sentenced Ward to life in prison after concluding that he had been planning a “catastrophic” terrorist attack and was “deeply committed to neo-Nazi ideology.” During his week-long trial in Edinburgh, Scotland’s capital city, it emerged that police had uncovered his plot by chance, after receiving a tip that he was trying to import weapons from the United States. Officers searched his home – and the home of his mother – and discovered his large armory, as well as a stash of 131 documents about Nazism, terrorism, and manufacturing explosives.

In April, a judge sentenced Ward to life in prison after concluding that he had been planning a “catastrophic” terrorist attack and was “deeply committed to neo-Nazi ideology.” During his week-long trial in Edinburgh, Scotland’s capital city, it emerged that police had uncovered his plot by chance, after receiving a tip that he was trying to import weapons from the United States. Officers searched his home – and the home of his mother – and discovered his large armory, as well as a stash of 131 documents about Nazism, terrorism, and manufacturing explosives.

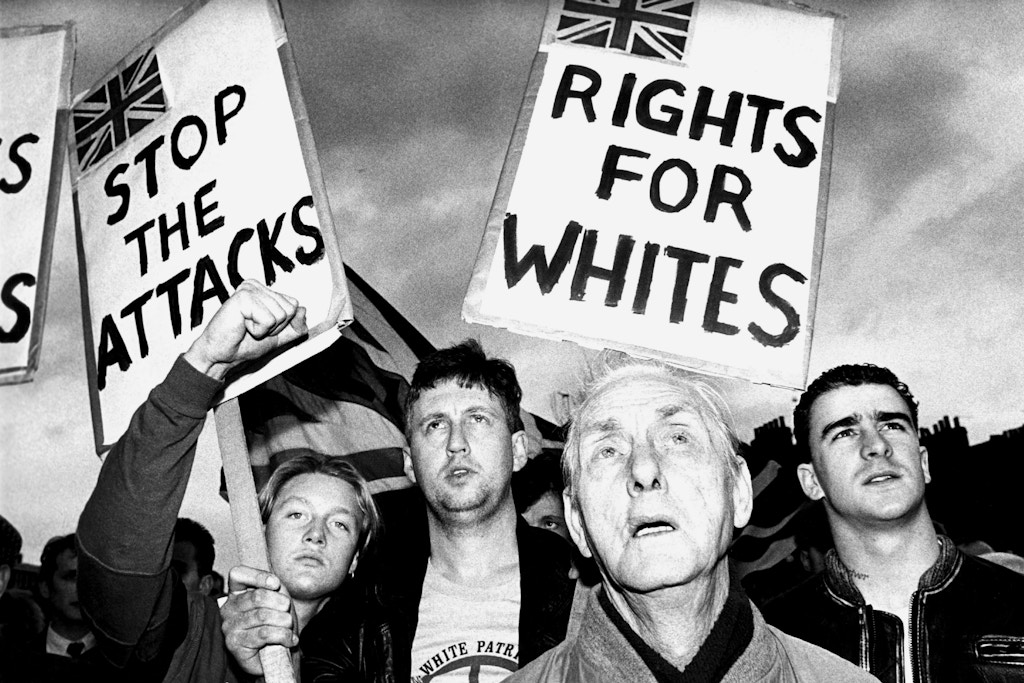

FAR-RIGHT EXTREMISTS have been active in the U.K. for most of the last century. In the 1930s, Oswald Mosley took inspiration from Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and launched the British Fascist Union, otherwise known as the Blackshirts. In bombastic speeches to audiences across England, Mosley ranted about “the organized corruption of press, cinema, and Parliament,” which he blamed on “alien Jewish finance.” Mosley campaigned against the U.K. going to war with Adolf Hitler on the grounds that “Jewish interests” were pushing for the conflict; instead, he advocated isolationist, “Britain first” policies. During the same period, groups such as the Nordic League and the Imperial Fascist League overtly supported Nazism. Like Mosley, they were anti-Semitic, but they went further, embracing Adolf Hitler’s concept of an “Aryan race.” The Nordic League rallied against what it called a “Jewish reign of terror.” The Fascist League’s emblem was the British Union Jack flag with a black swastika in the center.

Because National Action is now outlawed as a terrorist group, being a member of the organization is punishable by up to 10 years in prison. At least 14 people in the U.K. have so far faced terrorism charges connected to their alleged association with the group. Among them are two British Army soldiers, including 33-year-old Lance Corporal Mikko Vehvilainen, who was accused of being a National Action recruiter. Prosecutors said Vehvilainen commented regularly on a white supremacist internet forum where, under the name “NicoChristian,” he railed against black people, whom he referred to as “beasts.” In online posts reviewed by The Intercept, NicoChristian wrote that white people “shouldn’t even be on the same planet” as black people, and added: “The sooner they’re eliminated, the better.”

Because National Action is now outlawed as a terrorist group, being a member of the organization is punishable by up to 10 years in prison. At least 14 people in the U.K. have so far faced terrorism charges connected to their alleged association with the group. Among them are two British Army soldiers, including 33-year-old Lance Corporal Mikko Vehvilainen, who was accused of being a National Action recruiter. Prosecutors said Vehvilainen commented regularly on a white supremacist internet forum where, under the name “NicoChristian,” he railed against black people, whom he referred to as “beasts.” In online posts reviewed by The Intercept, NicoChristian wrote that white people “shouldn’t even be on the same planet” as black people, and added: “The sooner they’re eliminated, the better.”

AT THE EXTREME ENDS of the political spectrum, there is always a violent fringe. However, “there is clearly an increase in activity on the extreme right wing and you can see that from anecdotal evidence – the sort of incidents we’ve seen take place,” says Raffaello Pantucci, director of international security studies at the Royal United Services Institute in London. “It has always existed in the U.K. … but it’s always tended to be scattered and disorganized. What is worrying recently is we have seen it get more organized.”

TOMMY ROBINSON, WHOSE online posts were read by the London mosque attacker, was recently banned from Twitter for breaching its “hateful conduct policies,” but he remains on Facebook and YouTube, where he reaches a combined audience of more than 900,000 people. Robinson rose to prominence as the leader of a group called the English Defence League, a far-right organization that said it was concerned about “how non-Muslims are being marginalized” in British society.

Illustration: Adam Maida for The Intercept/Police Scotland/Getty Images

THE TOWN OF Banff on the northeastern coast of Scotland is a peaceful place, with just 4,000 residents and a picturesque bay that flows into the open sea. Fifty miles from the nearest big city, the air is fresh and the pace of life is slow. But for one young man, the town’s seaside location offered no contentment. He was stockpiling weapons and planning an act of terrorism.

Connor Ward lived in a gray, semi-detached apartment building a short walk from Banff’s marina, where dozens of small boats are docked and fishermen depart each day on a hunt for mackerel or sea trout. Inside his home, 25-year-old Ward was plugged into a different kind of world. He was reading neo-Nazi propaganda on the internet about an imminent race war.

Ward began preparing for the conflict. He purchased knives, swastika flags, knuckle-dusters, batons, a stun gun, and a cellphone signal jammer. He obtained deactivated bullets and scoured Google for information about how to reactivate them. From his Banff home, he purchased hundreds of steel ball bearings and researched bomb-making methods. He wrote a note addressed to Muslims that stated: “You will all soon suffer your demise.” Then he compiled a map showing the locations of mosques in the nearest city – Aberdeen – that he appeared intent on attacking.

Connor Ward, who was found guilty in March of plotting a terrorist attack targeting Muslims.

Photo: Police Scotland

Ward is just one individual, but his actions reflect a broader trend. British authorities say they are currently facing a growing terrorist threat from right-wing extremists, whose numbers have increased in recent years. Rooted in the notion that white European people are facing extinction, the extremists’ ideas have gained currency following a spate of Islamist attacks in Europe and a refugee crisis that has seen millions of migrants travel to the continent from war-torn Afghanistan and Syria.

In Austria, Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, France, Sweden, Hungary, and the Netherlands, far-right ideas have also surged in popularity. The same is true in the United States, where Donald Trump’s presidency has energized white supremacists. Far-right politicians and activists have successfully tapped into concerns about economic uncertainty, unemployment, and globalization. But they have built most of their support base around the issues of immigration and terrorism.

In June 2016, an act of brutal violence highlighted the burgeoning danger in the United Kingdom. In broad daylight in a small village in the north of England, 52-year-old white supremacist Thomas Mair pulled out a homemade rifle and shot dead Jo Cox, a member of Parliament. Mair saw Cox as a “traitor” to white people due to her pro-immigration politics. Six months later, for the first time in U.K. history, a far-right group was banned as a terrorist organization, alongside the likes of Al Qaeda and Al Shabaab. Since then, the problem has continued to spiral.

British police say they have thwarted four far-right terrorist plots in the last year. In a speech in London in late February, the U.K.’s counter-terrorism police chief, Mark Rowley, cautioned that far-right groups were “reaching into our communities through sophisticated propaganda and subversive strategies, creating and exploiting vulnerabilities that can ultimately lead to acts of violence and terrorism.” Police were monitoring far-right extremists among a group of some 3,000 “subjects of interest,” Rowley said, adding: “The threat is considerable at this time.”

FAR-RIGHT EXTREMISTS have been active in the U.K. for most of the last century. In the 1930s, Oswald Mosley took inspiration from Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and launched the British Fascist Union, otherwise known as the Blackshirts. In bombastic speeches to audiences across England, Mosley ranted about “the organized corruption of press, cinema, and Parliament,” which he blamed on “alien Jewish finance.” Mosley campaigned against the U.K. going to war with Adolf Hitler on the grounds that “Jewish interests” were pushing for the conflict; instead, he advocated isolationist, “Britain first” policies. During the same period, groups such as the Nordic League and the Imperial Fascist League overtly supported Nazism. Like Mosley, they were anti-Semitic, but they went further, embracing Adolf Hitler’s concept of an “Aryan race.” The Nordic League rallied against what it called a “Jewish reign of terror.” The Fascist League’s emblem was the British Union Jack flag with a black swastika in the center.

The defeat of Hitler, however, did not mark the end for the U.K.’s extreme right. Through the 1950s and 1960s, groups like the White Defence League and the Racial Preservation Society continued to espouse a bigoted ideology, spreading anti-Semitic conspiracy theories and demanding the curtailment of immigration. Between the 1970s and 1990s, the National Front and the British National Party carried on the trend, organizing demonstrations and campaigns that championed the idea that all non-white immigrants should be deported from the U.K.

Among the British National Party’s members was David Copeland, who worked as an engineer’s assistant on the London Underground. Copeland had grown up fantasizing about being a Nazi officer. By the time he was 22, he was teaching himself to design bombs. In April 1999, Copeland launched a series of attacks in London, placing sports bags packed with explosives and four-inch nails in three areas of the city where there were black, Asian, and gay communities. The devices caused carnage, killing three and injuring 140. Copeland later told police that he had intended to “spread fear, resentment, and hatred throughout this country; it was to cause a racial war.”

Today, the National Front and the British National Party still exist as political entities. But like most older far-right groups, they do not wield the influence they once did. Their membership has diminished, mostly due to a lack of leadership and internal conflict. Now a newer band of far-right extremists is replacing them. These newcomers share many of the same values as their predecessors, but a desire for violence is more widespread among them, which worries British police and intelligence agencies.

The group that was banned in 2016 as a terrorist organization – National Action – has advocated murdering politicians. In October 2017, an unnamed member of the organization was accused of plotting to assassinate Rosie Cooper, a 67-year-old Labour member of Parliament. The planned execution was allegedly sanctioned by National Action’s leader, 31-year-old Christopher Lythgoe. Two years earlier, in January 2015, one of National Action’s supporters attempted to behead an Asian man in a supermarket in the north of Wales, shouting “white power” during a frenzied assault with a machete.

From left Alexander Deakin, 22, Mikko Vehvilainen, 32, and Mark Barrett, 24, who were accused of being part of the organization National Action in Sept. 2017.

Image: Elizabeth Cook/PA Wire via AP

When police searched Vehvilainen’s quarters at an army camp in Wales in September 2017, they found Nazi flags, body armor, and a stash of weapons, including a shotgun, a rifle, a crossbow, arrows, knuckle-dusters, machetes, and daggers. The soldier also had a copy of the manifesto written by far-right terrorist Anders Breivik, who in July 2011 murdered 77 people in Norway. When police turned up at Vehvilainen’s home to take him into custody, he reportedly told his wife: “I’m being arrested for being a patriot.”

Last month, a jury at a court in Birmingham found Vehvilainen not guilty of stirring up racial hatred and possessing a terrorism manual. But he received an eight-year prison sentence for a separate offense: illegally possessing tear gas.

AT THE EXTREME ENDS of the political spectrum, there is always a violent fringe. However, “there is clearly an increase in activity on the extreme right wing and you can see that from anecdotal evidence – the sort of incidents we’ve seen take place,” says Raffaello Pantucci, director of international security studies at the Royal United Services Institute in London. “It has always existed in the U.K. … but it’s always tended to be scattered and disorganized. What is worrying recently is we have seen it get more organized.”

The British government operates a counterterrorism program called Prevent, one strand of which identifies people deemed to be at risk of being drawn into terrorism, usually because they have been reported to police for expressing extremist views. Since 2007, according to police and government statistics about the program, the number of people at risk of becoming involved in right-wing terrorism has increased each year. In the five years between 2007 and 2012, concerns were raised about 177 people on the far-right spectrum. Between 2012 and 2017, 2,489 individuals were added to the list. The spike in far-right extremism paralleled a surge in Islamist extremism. Between 2007 and 2012, 1,560 people were identified as vulnerable to becoming drawn into Islamist terrorism, according to police and government reports. Between 2012 and 2017, that number increased to 11,624.

It is unclear whether all of the people the Prevent program identifies pose a real threat, but the numbers do seem to reflect a broader phenomenon. “There is a sense that a culture war is happening,” says Pantucci. “We are seeing greater polarization in our public debate … We are seeing xenophobic views become mainstream. And that means the unacceptable edge, the violent edge, is getting pulled toward the center as well.”

“There is a sense that a culture war is happening.”

Since 2013, the rise of the Islamic State – paired with a wave of predominantly Muslim refugees traveling to Europe and North America due to the conflicts in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan – has galvanized the far right. In the U.K., ISIS-inspired terrorist attacks exacerbated ethnic divisions within communities and led to more reported cases of Islamophobic verbal and physical assaults. And when the U.K. voted in June 2016 to leave the European Union – in part due to concerns about immigration – that decision further emboldened the far right and triggered an upsurge in racially tinged hate crimes. All of these factors combined have created a fertile environment in which extremism has thrived.

For ISIS, the internet proved to be a vital recruiting tool. It helped the group spread its extremist messages to a global audience and enabled its supporters to connect with one another, even if they were thousands of miles apart. The same has been true for the far-right. The internet has fueled a new breed of “self-radicalizers” – people with no real-world connection to any extremist group, who instead consume online propaganda and decide to carry out a terrorist plot on their own.

“It is easier than ever before for people to access far-right content that ranges from moderate to the very radicalizing, extreme end,” says Joe Mulhall, a senior researcher with the London-based group Hope Not Hate, which studies the far-right. “The days of having to be involved in an organization to find the information are long gone. You can get it now with a few clicks wherever you are in the world.”

The extremist narratives peddled in terrorist propaganda are particularly potent for people who have experienced emotional trauma and substance abuse, research indicates. The case of Connor Ward, the young man from Banff in Scotland, is a possible illustration of that.

Ward was diagnosed with a personality disorder and he had a troubled family life. His father, Alexander Ward, is a convicted sex offender who impregnated Connor’s ex-girlfriend, according to court records. Ward despised his father for this and, in 2012, tried to build a bomb to kill him. Ward’s plot was discovered by his mother, who reported him to police. He was sent to jail for three years, but was released after about 18 months. During the same period, he developed an infatuation with Nazism and began planning his mosque attacks. His terrorism plan appears to have been driven at least in part by the far-right race war theories he discovered online.

Other cases bear similar hallmarks. Last year, 48-year-old Darren Osborne became radicalized after he watched a television program about a Pakistani child sex trafficking gang that had operated in the north of England. Within a few weeks, according to Sarah Andrews, Osborne’s former girlfriend, he became “obsessed with Muslims, accusing them all of being rapists and being part of pedophile gangs.” Andrews said Osborne began reading the social media posts of Tommy Robinson, a prominent figure on the British far right, who campaigns against what he calls the “Islamization” of the U.K. On June 19, 2017, Osborne hired a white Citroën van and drove it 150 miles from his home in Cardiff to Finsbury Park mosque in north London. He waited until local worshipers left the mosque after an evening prayer, then rammed his van into the crowd, killing 51-year-old Makram Ali and wounding 10 others. He left a note in his van that decried “feral inbred, raping Muslim men, hunting in packs, preying on our children.” According to Osborne’s sister, he was taking antidepressants at the time and had tried to kill himself weeks earlier.

A few days after Osborne’s attack, Ethan Stables, an unemployed 20-year-old from a small town in the north of England, was preparing to launch his own atrocity at an LGBT club night. Stables posted comments on a far-right Facebook group saying that he was planning to “slaughter every single one of the gay bastards.” Stables’s comments were reported to police, and when they searched his home they found a machete, an axe, and a bomb-making manual. He was convicted of plotting a terrorist attack. It emerged during his trial that Stables had been diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome as a child, and in September 2016, had become obsessed with Nazism. He used the internet to communicate with other extremists and researched how to prepare for a race war. He was unemployed and blamed immigrants for his problems. “My country is being raped,” he wrote in one WhatsApp message. “I might just become a skinhead and kill people.”

TOMMY ROBINSON, WHOSE online posts were read by the London mosque attacker, was recently banned from Twitter for breaching its “hateful conduct policies,” but he remains on Facebook and YouTube, where he reaches a combined audience of more than 900,000 people. Robinson rose to prominence as the leader of a group called the English Defence League, a far-right organization that said it was concerned about “how non-Muslims are being marginalized” in British society.

In 2013, Robinson stepped down as the English Defence League’s leader, saying that he was concerned about the “dangers of far-right extremism.” However, he has since continued to campaign on the same issues as a solo operator. His Twitter page, before it was suspended, offered a steady stream of posts that presented Muslims and Islam as existential threats to British and European society.

Rowley, the U.K.’s counterterrorism police chief, said Robinson was guilty of spreading “dangerous disinformation and propaganda” and claimed he was the right-wing equivalent of a British Islamist preacher named Anjem Choudary, who was jailed in 2016 for encouraging support for ISIS. During his February speech in London, Rowley said that Robinson was using his platform to “attack the whole religion of Islam by conflating acts of terrorism with the faith.”

Robinson did not respond to a request for comment; he has previously refuted allegations that his rhetoric could inspire right-wing terrorism.

In recent months, Robinson has established an informal alliance with a new group calling itself Generation Identity, which is actively trying to recruit members in the U.K. Generation Identity, a far-right youth movement that originated in France, campaigns against what it calls the “great replacement” – a theory that white European countries are going to be taken over by Muslim migrants. According to the group, “Islamic parallel societies” and mass immigration will lead to “the almost complete destruction of European societies within just a few decades if no countermeasures are taken.”

The image-conscious group has a slick website, publishes professionally produced videos, runs military-style training camps, and instructs its supporters that they must have a “well-groomed appearance.” Those who sign up to participate in its activities are personally vetted, and must fill out an application form that asks them to explain their political background and five favorite social media personalities. Prospective members of the secretive organization must sign a disclaimer stating that they are “not a journalist, activist, or informant meaning to record audio/video.”

The group insists that it is not extremist or racist. Instead, it claims it merely wants to preserve European national identity and calls itself “identitarian.” But beyond the glossy branding and semantics, Generation Identity is ideologically aligned with the far right. Its belief that migrants are going to extinguish white Europeans – unless white Europeans fight back – is reminiscent of the far right’s longstanding narrative about an impending race war. Unlike older far-right groups, however, which targeted Jews and black people, Generation Identity focuses its ire predominantly on Muslims.

“The ideology of Generation Identity is actually very extreme,” says Mulhall, the Hope Not Hate researcher. “They have been very clever in terms of their lexicon and language; they are trying to package extreme ideas in ways that are appealing to young people. So far, it is a strategy that has been successful for them, and that is worrying.”

Martin Sellner is the 29-year-old European spokesperson for Generation Identity. An Austrian who studies law at the University of Vienna, Sellner told The Intercept that “a combination of massive immigration, a low birth rate, and the politics of multiculturalism” were endangering European democracies. “The Muslim population will change the legislation, it will change the culture, and in the end will destroy the identity and the freedom we have in Europe,” Sellner said. He denied that he was a white supremacist, a racist, or an extremist, and said he disavowed violence. “I am just delivering a message,” he said. “I am just saying publicly what most people are afraid to say.”

On March 9, Sellner tried to enter the U.K. to give a speech in London, where a small group of Generation Identity members have been attempting to recruit. When Sellner arrived at England’s Luton Airport, however, he and his traveling companion, the American right-wing internet personality Brittany Pettibone, were not permitted to enter the country. Sellner was detained under the U.K.’s Terrorism Act and deported back to Vienna. Police told Sellner that his presence in the U.K. was “not conducive to the public good” because his planned public appearance would incite community divisions.

A week later, in the northeastern corner of Hyde Park in central London, about 400 people gathered for a demonstration. Robinson, the former English Defence League leader, had announced that he would give the speech that Sellner had been prevented from delivering. Among the crowd were men and women aged between their early 20s and late 50s, some of whom were rowdy and carrying Union Jack flags and placards with slogans like “Censor Islam Not Free Speech” and “I Will Hate What I Want.”

A police officer was struck in the face, either with a fist or an object. Blood streamed down his cheek.

Robinson arrived in a white van, flanked by several burly men wearing black jackets with “SECURITY” emblazoned on the back. The crowd began chanting Robinson’s name as he moved toward the park through a crush of bodies, a short distance from London’s famous Marble Arch.

Within a couple of minutes, there were screams and a flurry of pushing and shoving. A group of protesters – some of them shouting “Allahu akbar” – had faced off with Robinson’s supporters, and fighting broke out. Amid the melee, a police officer was struck in the face, either with a fist or an object. Blood streamed down his cheek. Barely able to maintain his balance and looking dazed, the officer was hauled out of the throng of bodies by one of his colleagues and placed into the back of a silver police van, where he slouched against a seat and held a thick white bandage across his face to soak up the blood.

Before Robinson was able to speak, a middle-aged man wearing a dark green hat and a white shirt attempted to stand on a box to declare his opposition to the former English Defence League leader. The crowd, which moments earlier had been chanting “free speech,” hurled abuse at the man, launched cans of beer at him, and pulled his hat from his head. There were shouts of “shut your face!” and “fuck off!” while the man, looking flustered, was pushed off the box and shoved back into the crowd.

Robinson, wearing blue jeans and a black jacket, handed out paper copies of his speech and then began reading it aloud. “No to Islamization!” he shouted to cheers. “No to mass immigration and the great replacement!”

“Tyranny has locked you in since the days of your childhood,” he said. “I ask you, I command you: Break free! Patriots of the U.K., come out of the closet. Make your dissent visible by acts of resistance that inspire others!”

Robinson concluded with a warning for the British government, saying that it could “ban the speaker but it cannot ban the speech.” By blocking Sellner and other far-right activists from entering the country, he said, the government had “relit the fire and the fight of the British people.”

Robinson pushed his way through the crowd, back to the sanctuary of his white van. Some of his supporters stayed behind at Speakers’ Corner. Generation Identity activists handed out leaflets that explained their support for the “preservation of the ethno-cultural identity.” Near a fence at the perimeter of the park, several young Arab men gathered behind a small stall, where they were giving out information about the Quran. A group of men who had attended Robinson’s speech approached them.

“That so many crimes have been committed by Muslims is proof that you are causing disproportionate harm to our society,” shouted one of the men, a 26-year-old named Jamie, who was wearing black-framed glasses, a black jacket, and blue jeans. “Your religion is not good for Britain.”

“Well, we’re still here and we’re not going nowhere,” replied Asem, a 29-year-old Muslim man, who said he’d been born and brought up in north London. He had a trimmed beard and was wearing a gray tracksuit and a green baseball cap. “So what are you going to do about me? I haven’t got anything on my [criminal] record,” he said. “For you to generalize [about] us as a religion is bullshit.”

The argument continued for about 10 minutes until neither side had anything left to say.

“I don’t have no time for this,” said Asem. He turned and walked away, followed by a group of about six of his friends.

“Yeah, go home!” said one of the young Robinson supporters, who walked off in the opposite direction.

The scene was a portrait of the deep divisions that exist in this disunited kingdom. As the sun went down over Hyde Park, snow began to fall. The crowds dispersed, trampling over the broken glass and discarded placards strewn across the ground.